CUA and TRM

Prologue

I feel nothing but disdain for acronyms. That is why I shoved a couple out of my mind and into the title. Pompous CUA stands for Complexity, Uncertainty, and Ambiguity—which I use as a proxy for the unpretentious environment that surrounds me wherever I’m working. Obnoxious TRM stands for Task-Relevant Maturity—which I use as a proxy for my unassuming expertise in relation to whatever work I’m doing. Then, you may ask, why not simply use environment for CUA and expertise for TRM? Well, I emphasised the word proxy in those earlier sentences for a reason. CUA and TRM have advantages in being unique, whereas each corresponding generic word is like an umbrella that shelters bickering bipeds who are standing cheek by jowl. Hence I’ll refrain from excessive generalisation, as it’ll unleash misleading equivalence among distinct meanings. CUA and TRM are thus two terrible terms with whom I’m willing to share my umbrella in the thick of torrential rain. Yes, it’s an alliterative abuse of irony indeed. Or, as I like to silently shout: “Jeer at Janus!” (I am referring, of course, to the ancient Roman god with two faces.)

I’m parading CUA and TRM in this essay because they constitute a thinking tool which I’ve found useful for many years. I cannot promise that this tool will be useful for you as well—since the reality is that it’ll probably be the opposite. But I can say that it’s worth scrutinising in case it helps you invent something better for yourself. I operate it like an intuition pump, as in the ingenious concept from the late great philosopher Daniel Dennett (read the eponymous book from 2013). For me the pump runs in a succinct sequence: first, I assess my CUA; second, I judge my TRM; then, I select a strategy based on the combination of my CUA and TRM scores; finally, I apply that strategy to the way I work. However, to be clear, I’m not implying game theory when I use the word strategy. Instead, I mean just a conscious decision to work in a specific way, rather than all the other ways which might occur to me at that moment.

You may begin to ponder the components that make up the pump, and you should take it apart in order to improve the whole gizmo. These components are enduring questions, which you can contemplate about your work to gain insights. What cognitive costs and benefits might CUA or TRM encompass in your line of work? How would you intuitively assess and assign a score to each? Does the exact order of the steps matter in the sequence I outlined? Can AI help in any of the steps? When and how does this intuition pump “blow up” so that you can protect yourself?

Grove’s Grounding

Let me first disabuse you of any hint that I invented CUA and TRM. I learned both concepts from a book called High Output Management (1995, 2nd ed.), written by the legendary Andrew Grove, who ran Intel during the 1990s. Grove’s life is an inspiration to computer engineers like me, given his humble beginning and incredible survival story in Hungary. His writing style is always straight to the point, and I really want more of it in this genre. His principles of management are constantly grounded in a commercial reality where competition is king. He forgoes all the airy-fairy, handwavy, phony baloney corporatese which flood the pages of company reports (you know, lucid language like “leverage synergies to deliver sustainable outcomes for all stakeholders”). He describes CUA as a way of assessing an environment in which people work:

An imaginary composite index can be applied to measure an environment’s complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity, which we’ll call the CUA factor. Cindy, the process engineer, is surrounded by tricky technologies, new and not fully operational equipment, and development engineers and production engineers pulling her in opposite directions. Her working environment, in short, is complex. Bruce, the marketing manager, has asked for permission to hire more people for his grossly understaffed group; his supervisor waffles, and Bruce is left with no idea if he’ll get the go-ahead or what to do if he doesn’t. Bruce’s working environment is uncertain. Mike, whom we will now introduce as an Intel transportation supervisor, had to deal with so many committees, councils, and divisional manufacturing managers that he didn’t know which, if any, end was up. He eventually quit, unable to tolerate the ambiguity of his working environment.

Grove doesn’t turn CUA into an obsessive metric in the book. Rather, he uses it in a purely coarse-grained manner with the binary values low and high. He argues that it’s a manager’s job to first setup, and then periodically adjust, the CUA factor. For instance, he explains that a new hire needs to be assigned a low CUA job initially so that it allows the person to grow with experience. He thus promotes graduate recruitment: “Bring young people in at relatively low-level, well-defined jobs with low CUA factors, and over time they will share experiences with their peers, supervisors, and subordinates and will learn the values, objectives, and methods of the organization. They will gradually accept, even flourish in, the complex world of multiple bosses and peer decision-making.” However, he’s realistic about hiring new senior staff:

But what do we do when for some reason we have to hire a senior person from outside the company? Like any other new hire, she too will come in having high self-interest, but inevitably we will give her an organization to manage that is in trouble; after all, that was our reason for going outside. So not only does our new manager have a tough job facing her, but her working environment will have a very high CUA. Meanwhile, she has no base of common experience with the rest of the organization and no knowledge of the methods used to help her work. All we can do is cross our fingers and hope she quickly forgets self-interest and just as quickly gets on top of her job to reduce her CUA factor. Short of that, she’s probably out of luck.

Grove articulates that the work environment is crucial in determining how a person performs. But simultaneously, the person’s capabilities are equally crucial. And he defines this as TRM:

Some researchers in this field argue that there is a fundamental variable that tells you what the best management style is in a particular situation. That variable is the task-relevant maturity (TRM) of the subordinates, which is a combination of the degree of their achievement orientation and readiness to take responsibility, as well as their education, training, and experience. Moreover, all this is very specific to the task at hand, and it is entirely possible for a person or a group of people to have a TRM that is high in one job but low in another.

This leads to a mutual interplay between TRM and CUA. Grove shares an example: “a person’s TRM can be very high given a certain level of complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity, but if the pace of the job accelerates or if the job itself abruptly changes, the TRM of that individual will drop. It’s a bit like a person with many years’ experience driving on small country roads being suddenly asked to drive on a crowded metropolitan freeway. His TRM driving his own car will drop precipitously.” He again adopts a coarse-grained scale for judging TRM so that the combination of CUA and TRM will form a small matrix. He doesn’t actually provide such a matrix in the book, but his elucidations are clear that it exists and that it’s a structured way to think about how we work.

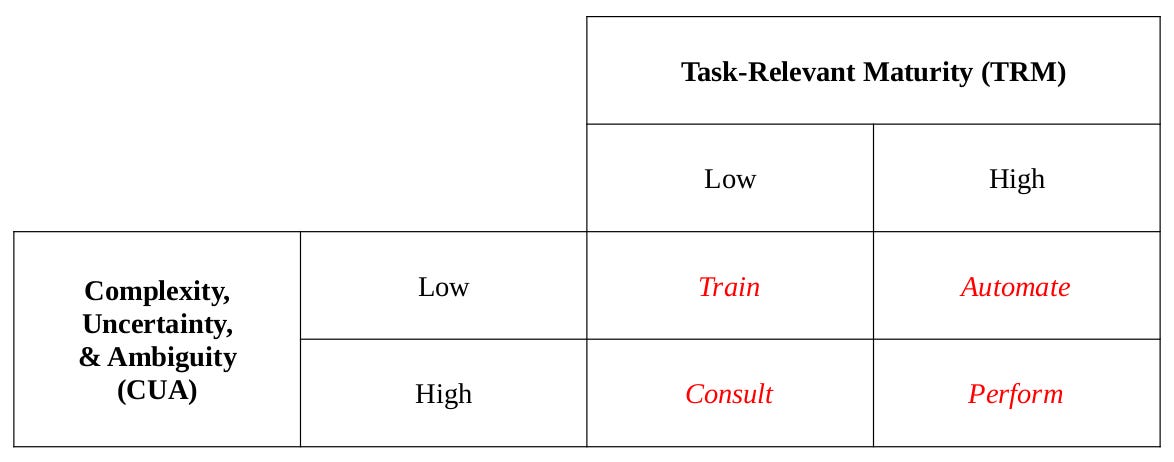

While Grove tries to empower managers in the book, I want to empower individuals to make smarter decisions. Hence my focus with CUA and TRM is on how to intuitively assess each factor and assign a binary value. Suppose that we have solved this how to challenge, then the result is a classic 2x2 matrix with four quadrants—each containing a predefined strategy—from which we can select one strategy that’s matched to the task we’re doing within the environment surrounding us. There’s no universal set of strategies that will succeed for all. Instead, ponder what your work demands in each quadrant and use that insight to design better ways of working.

Fast and Frugal

Now let’s address the how to challenge. We need an intuitive way to assess CUA and TRM so that we can assign either a low or a high value to each factor. The purpose of intuition is to make rapid and effortless decisions. This is not about executing an elaborate flowchart. In fact, no external aid is required for this thinking tool—not even pen and paper! The way I’ve learned to solve this is by using fast-and-frugal heuristics invented by the psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer and his colleagues. Gigerenzer has been writing on this topic for thirty years. I recommend his recent book The Intelligence of Intuition (2023), although he covers this idea in prior books and articles.

I also defer to Gigerenzer and other notable psychologists, mainly Gary Klein, to vigorously defend the value of intuitions. There is a legitimate criticism that intuitions are unreliable—but mostly for a novice who hasn’t yet developed the correct intuitions and who doesn’t yet know how to ring-fence the reliability of intuitions. In my experience as a computer engineer—it is certainly possible to develop the right intuitions while knowing exactly when and how they fail. I started out standing at the bottom of a cliff. Then I climbed the rock face leading to a narrowly defined domain of expert intuitions. I’ll circle back to this point about limitations in the epilogue.

My fast-and-frugal heuristic for discerning high CUA from low CUA is to pick any of the three environmental cues—complexity, uncertainty, or ambiguity—and make it the decider for assigning a high value. In other words, if just one of the three cues is high in my judgement then the whole CUA is high. No need to go any deeper into the decision tree. Conversely, CUA is low only when all three are low in my judgement. I emphasise that this is my judgement because I’ve deliberately biased the heuristic to catch high CUA more than low CUA. As per Grove’s example of Cindy, Bruce, and Mike: there are disordered cues in the environment which constitute its CUA. Occasionally all three will be concurrently conspicuous. Often only one will barely be noticeable. And I want to reliably catch the dangerous high CUA situation so that I can use the appropriate strategy afterwards to deal with the danger.

My motivation for this bias toward detecting high CUA is that the cost of a mistake is huge for me. I cannot afford the ruinous consequences of messing up in a high CUA scenario. And sagely dealing with such an asymmetry is a key part of my mindset. But it does not mean that you should adopt my bias! Think about what is better suited to your work environment so that you can tailor a heuristic for yourself, and uncover its hidden biases.

There’s still one big piece undefined though: what exactly is complexity, uncertainty, or ambiguity? Grove’s example is again informative. Cindy, Bruce, and Mike are in dynamic environments which require that they study the patterns present in their surrounds and recognise any recurring cues when deciding their CUA factors. There’s no formula unfortunately. You should develop a probing familiarity with your work environment, since no one else can do that as good as you. A rule of thumb that I apply is to detect key changes in people and places. I’m stating the obvious in saying that people and places form the elementary fabric of all work environments. If a bunch of new folks turn up at the office then it’s safe to say CUA is high that day. If visiting a new client’s premises then it’s automatically high CUA for the duration of the trip. I also consider the cost of an error as a critical guide in terms of asymmetry. Benefits typically don’t have the same absolute magnitude as costs. A careless mistake can be extremely expensive in whichever way I cost it, whereas several aggregated benefits would then be required to balance out the single lapse in judgement.

Moving on to TRM assessment: I usually find that it’s easier than CUA. Part of the reason is what Grove said in his definition: the education, training, and experience of a person are intrinsic signals. However, they can be biased. Hence feedback from an honest mentor can provide calibration. In essence, any type of work that has regular patterns—which includes most types of work—will make itself amenable to a TRM self-assessment off the back of increasing experience and expertise. But there’s still no formula. You have to scrutinise the work you do, and decide what are the right criteria for your own TRM decision. One warning that I heed is language. Regardless of the level of expertise for a task, it’s worth being sensitive to subtle changes in language about the task and its environment. I repeatedly assert in my essays that language is a noisy channel, because I’ve suffered the perils of naively trusting a vanishingly faint signal called meaning, which is something that people think they’re reliably communicating with words, but in reality they’re deluding themselves. So your TRM is low for a task whenever you feel confused by the words you’re hearing or reading about it—even if you’re the world’s only expert at doing that job!

Earlier I posed the question whether assessing CUA first or TRM first would make any difference. It does make a difference. You should judge CUA first, then TRM. Revisit the examples from Grove once more. The experienced driver with his own car in two different environments must still assign a separate TRM score to each driving task. It’s certainly tempting to treat the task independently of the environment, but that’s fraught with danger! We rarely control our environments, while we have reasonable control over our tasks. Therefore assess CUA first. Always.

My Strategies

Here are my strategies to populate the empty quadrants I showed earlier.

I use simple verbs that I remember easily, and which help me focus on my actions. I train myself when CUA is low and TRM is low. I automate as much as possible when CUA is low but TRM is high. I consult peers and mentors when I’m a nervous newbie in a high CUA situation with low TRM. And I perform using all my experience and expertise when my TRM is high despite being in a high CUA scenario. I repeat—these are my strategies. They have tangible benefits for me alone. You have to figure out for yourself if any of these will either help or hinder your work. But I’ll clarify couple of details in the hope of helping.

Training is inquisitive learning in the way I approach it. I prioritise quiet time for reading books, scholarly journals, and reliable blogs. I conduct proactive experiments for any work that I am doing, which is learning via trial and error. So I try to carve out a low CUA sandbox for myself, where the consequences of failed experiments are mitigated. This is also a constructive way to think about schools, which are low CUA sandboxes for students who naturally have low TRM.

Automation is much easier said than done. It requires discipline, skill, and focus—because the goal is to offload repetitive yet complicated tasks to a suitable combination of hardware and software. A lot of hours in my career went towards automating the rigorous testing of my designs as an upfront investment. It’s an engineering philosophy commonly known as test-driven development. Building tools and constructing infrastructure is a big part of what I do in trying to improve my productivity. AI has gatecrashed all discussions of productivity these days, so I’ll tackle that topic next.

Can AI Help?

My short answer: “It depends.” I encourage always scrutinising and stress testing every new AI technology until it openly fails in your line of work. Only by examining the failure modes can any new technology be correctly understood, and consequently trusted. So in each quadrant of the CUA and TRM matrix you might find little pockets where a suitable piece of AI works well for you. But you would only know that by first making that piece of AI fail, and thereby learning for yourself where the strict boundary lies.

Gigerenzer uses the instructive concept of a stable-world. AI ought to be reliable inside a stable-world with low CUA, where the costs of failure are either negligible or tolerable. The typical example is a game with formally defined rules where AI can beat humans, given a stable-world with static search space of huge size, as in Chess and Go. This is demonstrably true when you really dig into how AI is trained by the main companies and how their apps fail measurably in the unstable real-world. Hence I look for little bubbles that wrap stable-worlds in all quadrants of the CUA and TRM matrix. I still use my strategies in how I work, but now I have an extra tool that I may exploit after I’ve conducted my own due diligence.

Another way to think about AI is that it’s your employee and you’re its manager. Thus what Grove says in his book could be turned around and applied to emerging AI Agents, which will presumably obey humans—and not vice versa! I’m adopting this perspective more and more as I have to setup a suitable CUA factor for whichever AI Agent I wish to evaluate. My initial stance is that every AI Agent has low TRM by default. Therefore, I must find the right tasks which it can perform for me while I supervise. And in that regard, Grove’s book now has new relevance.

Epilogue

An intuition pump is most beneficial when you realise how it overheats. Subsequently, you train yourself to prevent it from blowing up. Or that’s what I try to do anyway. The CUA and TRM matrix has limitations as a matter of course, and there are potential extensions, too. The art is in figuring out when not to use it. I practise this by visiting two imaginary countries that Nassim N. Taleb describes in The Black Swan (2010, 2nd ed.). There is Mediocristan. And there is Extremistan. But, never the twain shall meet!

Everything in this essay so far is meaningful only when you’re in Mediocristan. That’s the land irrigated by bell curves so that stupefying outliers cannot exist. A classic example from there is the height distribution of human adults. You’ll never meet someone ten times taller than the average adult, because that’s a biological impossibility. In stark contrast, however, Extremistan is oppressed by the iron grip of power laws. Wealth inequality is an example from there. Suppose that the richest ever human moves to a middle-class suburb. As a result of that one person’s street address changing, the average wealth of the middle-class suburb instantly jumps by at least ten times. Don’t use the CUA and TRM matrix when you’re in Extremistan. Forget it.

If you’re thinking about a fine-grained scale for CUA or TRM: also forget it. You’ll only be indulging a false metric which will perfectly overfit your small data. And that’s how you end up taking a one-way trip to Extremistan when you could have holidayed in Mediocristan. If you truly need more granularity than four quadrants: I recommend separate matrices for different purposes. If you work from home for part of the week and visit an office for rest of the week, as an example, you might benefit from having a separate matrix for each location. Same logic holds for multiple jobs, distinct projects, or disparate teams. You will then encounter a natural limit as to how many contexts you can lug in your head and still intuitively switch from one to another. My own limit is three. Actually, I’ve never gone beyond two in practice, although I carefully tested three so that my mind will cope if I ever find a need for three. Four fried my mind.

Another way to think about granularity is in terms of a hierarchy of matrices. That’s how I deploy my couple currently. One is for general top-level use, as I’ve described in this essay. The other is for AI stable-worlds, which I’m tuning and refining over time so that I can effortlessly invoke it from any given quadrant of my top-level matrix. But one final warning: don’t go deeper than two levels in such a fractal nesting, because intuition falls fast asleep and…begins…to…drea…